In 2005, Reggie Bush was college football’s golden child. He was electric, unstoppable, and the face of a USC dynasty that felt more Hollywood than collegiate. He was a Heisman Trophy winner.

…and yet just 5 years later, after reports surfaced that Bush and his family had accepted “impermissible financial benefits” from third parties, USC was hit with heavy sanctions, and Bush — one of the most transcendent players the sport had ever seen — was forced to vacate his Heisman Trophy.

What a different college football world we live in today.

The New College Football Reality

Thanks to the (likely) $2.8 billion NCAA/House settlement, schools will soon be allowed to pay players directly. Starting with the 2025-26 year, schools may pay up to $20.5 million to their athletes. This $20.5m amount is pegged at 22% of certain sports revenues and is set to rise annually by about 4% per year.

Crucially, this new pool of funds is not divided equally among all sports or athletes – schools have full latitude when deciding which sport, and which players, are to receive the funds. If a school spends $20.5m on the football team, though, there will be no school funds left over to pay players on the men’s or women’s basketball (or any other sport, for that matter).

In addition to funds paid directly by the school, players can also receive NIL dollars. NIL deals will now be reviewed by a third party — the consulting firm Deloitte — to ensure that they reflect fair market value. Going forward, all NIL deals above a modest threshold (deals $600 or greater) must be reported to and approved by a clearinghouse run by Deloitte. This clearinghouse will evaluate whether a proposed endorsement or NIL arrangement corresponds to fair market value for the athlete’s services or publicity. Deals that appear out of line (for instance, a local business paying a benchwarmer $500,000 for a few autograph sessions) could be flagged as disguised pay-for-play and be killed. Simply put, the NCAA will strike down deals that are used to circumvent the $20.5m salary cap. By funneling major booster contributions into the official cap structure and scrutinizing outside payments, the system aims curtail the influence of NIL-only money.

Interestingly, conference commissioners have been told that more than 75% of NIL deals over the last few years would likely be rejected by Deloitte as not reflecting fair market value. Therefore, NIL will presumably take on a much, much, much smaller role in college athlete compensation going forward.

[As a quick aside, there’s been some question about whether the clearinghouse will have the authority to prohibit disallowed NIL deals from going forward. This is still an open question – obviously, if the clearinghouse can’t prohibit these “disallowed” NIL deals from going forward, then nothing will really change from an NIL perspective. This speaks to the necessity of Congressional action on all of these college football regulatory issues, but that’s another post for another day.]

Going forward and assuming the clearinghouse can prohibit disallowed NIL deals from going forward, it’s fair to think of NIL deals as more akin to endorsement deals for pro athletes. The most marketable college players (e.g. a charismatic player on TV all the time because he plays for Deion Sanders) will still score sponsorships with national brands — see Shedeur Sanders and his NIL deals with Nike, Louis Vuitton and Delta Airlines. Those deals have a clear promotional value and should pass FMV tests. What will diminish are the opaque “appearances” contracts that were basically pay-for-play.

For CU players, getting NIL back to its original intent will be a good thing. CU is one of the most high profile football programs in the country, and national brands want to be associated with Deion Sanders and the CU football program. This means that they’ll have more “legit” NIL opportunities than players for most other football programs. Julian Lewis, for example, has already signed a 6-figure deal with Leaf Trading Cards as well as endorsement deals with men’s jewely band Jaxxon and also with Alo Yoga.

The Georgia Approach

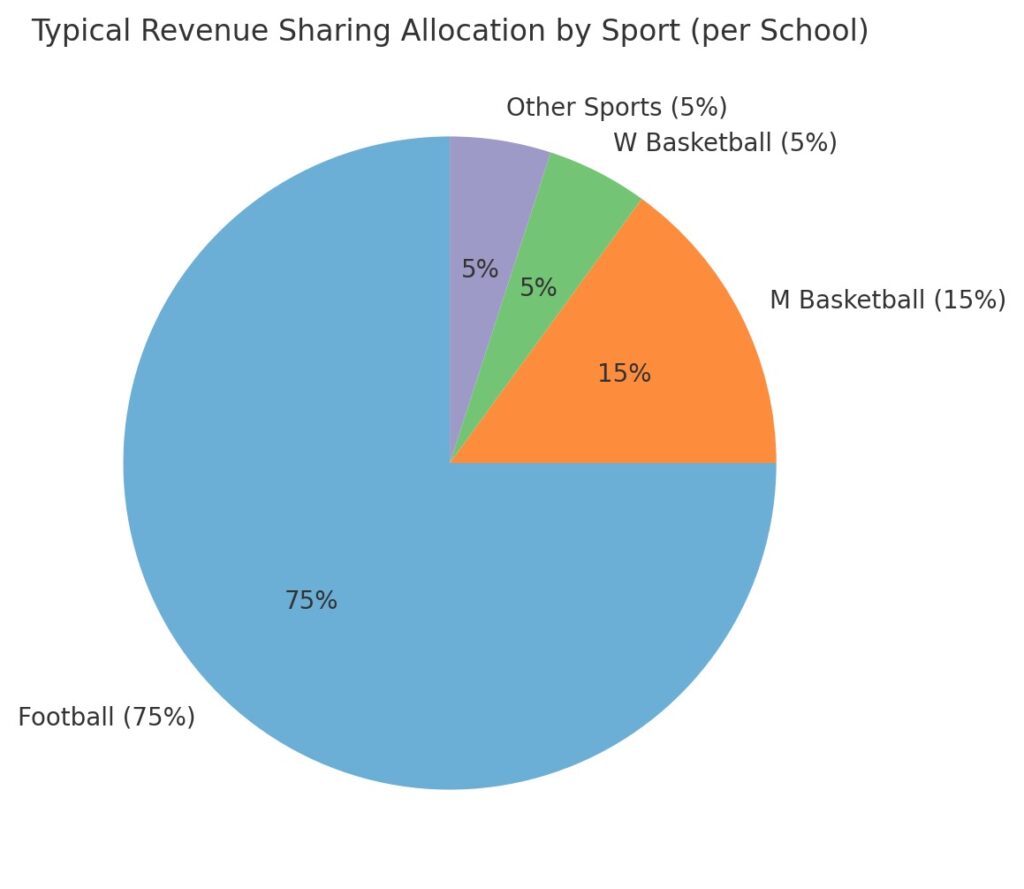

While the NCAA/House settlement does not mandate a fixed internal split between sports, a common approach (called the “Georgia Allocation”) has quickly emerged across the college landscape: approximately 75% of the pool will be slated for football, 15% for men’s basketball, 5% for women’s basketball, and 5% for all other sports. This 75/15/5/5 model reflects the reality that a handful of sports generate most of the income, and it mirrors what schools like Georga, Ohio State and Alabama have publicly announced in preparation for the new model.

One notable nuance: some schools have considered more egalitarian splits than 75/15/5/5. Industry chatter indicates a few schools floated a 50-50 split – i.e. half the money to football and half to all other sports — or a 60-40 split favoring football slightly more. These approaches might appeal to institutions emphasizing broad-based athletic success or addressing gender equity concerns. However, the competitive pressures of top-tier football make such even splits rare; most powerhouse programs seem intent on feeding football as much as possible without running afoul of Title IX (the Trump administration has issued guidance that says Title IX does not require “equal” distribution of the $20.5m between men’s sports and women’s sports). In any case, even at 50-50, football would still receive a vastly larger absolute sum than it does today since today it receives zero from direct pay.

It’s also important to note that schools must fund this $20m+ expense from their budgets, and that not all universities are equally positioned to do so. Many athletic departments are already stretched thin, and school athletic departments are taking different attempts at raising money. The University of Tennessee, for example, is adding an entertainment tax on football tickets starting in 2025 specifically to help fund the revenue-sharing payouts. The University of Iowa asks fans to “round up” every concession purchase or T-shirt purchase with the extra dollars going to the $20.5m pool. Other schools are taking a more direct approach and soliciting additional donor contributions earmarked for athlete compensation, essentially asking boosters to shift donations from unofficial NIL collectives into official athletic department channels.

From CU’s perspective, the Buffs are fortunate to have a surge of donor and fan interest since Deion Sanders’ arrival, which could translate into increased revenue to support the full $20.5M pay capacity. We have heard through the grapevine that the primary holdup on Deion Sanders signing a new contract with CU was that Sanders wanted assurances from the university that it would fund the full $20.5m pool while he was the head coach. He received such assurances. This is good news, and is indicative of the support that Todd Saliman has pledged to Rick George and the rest of the CU athletic department.

NFL Style Front Offices

With all of these drastic changes, college football is looking more and more like the NFL. It’s smart for teams to think about the $20.5m pool as akin to the salary cap in the NFL. Coaches aren’t just responsible for “simply” recruiting and developing anymore; they’re also managing roster construction under a salary cap. To keep up, many schools are reshaping their football administration. Just in the past week, Northwestern hired Christian Sarkisian, a Bengals scout (no relation to Steve), as their football general manager — a role that now includes cap management. Michigan’s Sean Magee came from the Chicago Bears’ front office. Nebraska brought in Pat Stewart from the New England Patriots. Stanford hired former Indianapolis Colt Andrew Luck. Colorado, for its part, has Reggie Calhoun Jr. serving as its Director of Football NIL/Revenue Sharing—a vital position in the new college football economy.

Reggie Calhoun Jr. is leading the charge for CU from a roster management standpoint.

CU fans need to be aware of the good work that Reggie Calhoun Jr. is doing for the football program. Calhoun Jr. created and developed the College Athlete Revenue System and the Navigator System, two software tools that map out NIL dollars (and roster construction) with a systemized approach to revenue share modeling, contract structuring, brand valuation, automation and operational controls. Calhoun Jr. also served as the Senior Executive of Athlete Development at RPA College. [Not to go down a giant rabbit hole, but RPA College has been criticized as the “Bishop Sycamore” of college. See the following link for mre:

For the record, I know nothing about RPA College and I’ll leave the sleuthing to those of you with more time on your hand.]

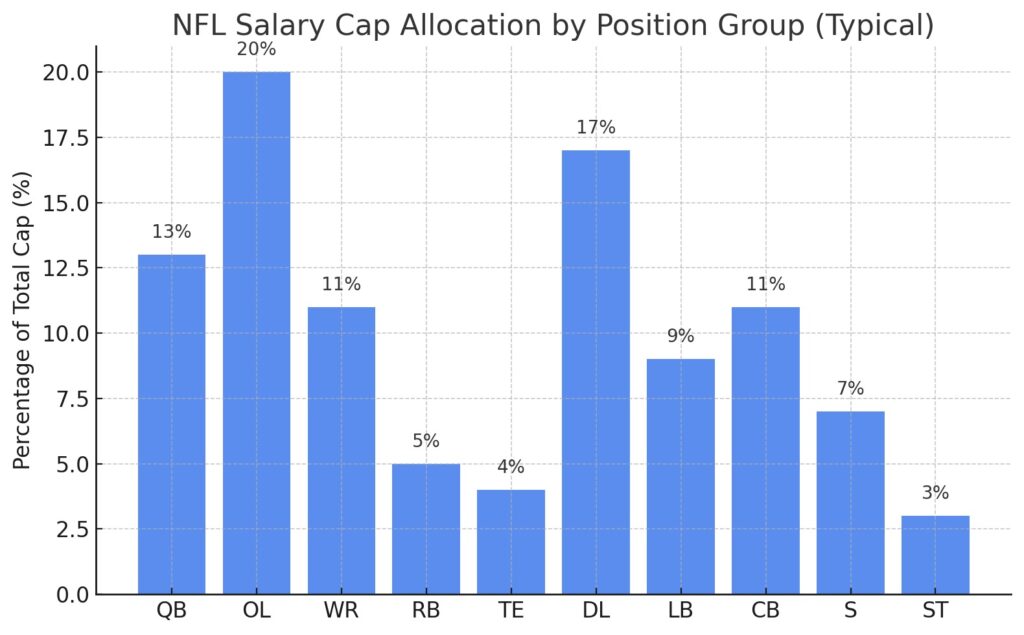

In the NFL, teams do not pay all players equally; they allocate salary cap resources strategically, prioritizing positions that contribute most to winning. While exact spending patterns vary by team, there are well-known positional value tiers. Quarterbacks are widely regarded as the most critical assets and thus consume the largest chunk of payroll. Protecting and supporting the quarterback is also vital, so left tackles and the offensive line unit, as well as top wide receivers, are high on the list. On defense, pass rushers (often edge defenders on the defensive line) and shutdown cornerbacks are premium positions that get big contracts, reflecting their impact on disrupting opposing offenses. By contrast, positions like running back or specialist roles (kickers, punters, etc.) tend to be lower paid in today’s game, because effective contributors can be found more readily and their impact is considered less central to team success. These market realities have led to a rough distribution of NFL salary cap spending that many analysts summarize as follows: quarterback ~10–15% of cap; offensive line ~18–22% (collectively); wide receivers ~10–12%; defensive line ~15–18%; cornerbacks ~9–12%; linebackers ~8–10%; safeties ~6–8%; tight ends ~3–5%; running backs ~4–6%; special teams ~2–4%

Unique Issues for Colleges

It’s worth emphasizing that while the NFL model is instructive, college teams will have their own unique considerations. For one, college rosters are much larger (up to 105 players, although CU is currently at about 72) than NFL rosters (53 active), so the budget must stretch over more individuals. This likely means the distribution within a position group could be flatter — e.g. an NFL team may pay one left tackle $15M and the backup $1M, whereas a college team might have several linemen each getting mid-range amounts since talent gaps are smaller or playing time is more evenly split among rotations. Additionally, locker room dynamics in college might push coaches to spread the wealth a bit to maintain morale among unpaid players-turned-paid employees. The presence of the transfer portal as quasi-free-agency will also influence allocation: college teams might need to overpay certain positions in a given year if they have an urgent roster hole and a prime transfer target available. This could temporarily skew the percentages (for instance, a program might spend an outsize chunk on a quarterback one year if that’s the missing piece, even if it means devoting 20%+ of the budget to QBs that season).

Another issue that is unique to college football (vs. the NFL) is the question of whether a program should lean on high school recruiting or the transfer portal. The portal has increasingly become the college equivalent of NFL free agency; like in the NFL, it often leads to overpaying for players due to scarcity and experience. Proven talent should cost more, but with a hard-ish cap in place, programs simply can’t afford to fill their entire roster with transfers. If you were a CU fan hoping they’d go after a higher-profile QB than Kaidon Salter in the portal, consider this: Carson Beck is rumored to be making over $4 million to play at Miami next year. Darian Mensah reportedly secured $8 million over two years at Duke. John Mateer is rumored to be making $3 million to play for Oklahoma. If the $15.375M football cap were already implemented, the$4 million rumored to be paid by Miami next year for Carson Beck equals 26% of the entire budget! By comparison, Dak Prescott — the highest-paid NFL quarterback by cap percentage — takes up “only” about 21% of the Cowboys’ salary cap. On the flip side, high school recruiting offers better value per dollar. Quarterback Bryce Underwood, last year’s No. 1 recruit, is rumored to be making around $2.5M — about 16% of a football team’s cap. That’s equivalent to what a Matthew Stafford–tier quarterback would cost: expensive, but manageable (Stafford actually makes 16% of the cap each year, 15th among QBs).

Think of it this way — you could get Beck at $4m for 1 year (presumably) vs. Underwood at about $10m for 3-4 years. The Underwood deal is the better deal from our perspective, and the kind of deal reflects each program’s team building approach. Miami is splurging on a 1-year star, while Michigan is investing in a player that might or might not be a star but that could be very good for a long time at less money per year.

From CU’s Perspective — What Approach Makes Sense?

Deion Sanders brought in Kaidon Salter, a quarterback from Liberty University. Salter isn’t a household name like Beck, but he’s a talented dual-threat QB who shined at the Group-of-5 level. Reports pegged Salter’s NIL valuation around $590,000 by the time he joined Colorado, reflecting a steep rise (about +$95k) in his market value over the previous year. For Colorado, Salter represented a more cost-effective option than chasing a bigger name. Even if he’s receiving, say, $1m, he’s still relatively affordable against the cap, and as a fifth-year senior he brings experience.

Additionally, JuJu Lewis has an On3 NIL valuation (taking into account his value against the salary cap) of about $1.2m. CU could be getting a top-end QB talent for a quarter of the cost of some transfer options. In a cap-constrained system, this kind of value could be the key to sustainable success

In sum, Colorado chose a middle path: a solid transfer at a moderate price rather than a superstar at an exorbitant price or a green freshman who might not be ready. This aligns with where Colorado is as a program — building depth and trying to become bowl-caliber before perhaps making the jump to playoff contention down the line. If Salter performs well, Colorado gets good value. If he underperforms, the Buffs haven’t crippled their budget and can pivot to JuJu Lewis.

In a cap-constrained system, these kinds of valuable adds could be the key to sustainable success. This isn’t to say Deion Sanders should avoid expensive portal additions altogether. He can and should continue to supplement the roster with transfers — he just has to be strategic about it. Finding under-the-radar contributors, such as DJ McKinney, is essential. McKinney wasn’t a major portal headline but became a very, very good defensive starter at a more reasonable price point. That’s the kind of move that wins in a capped environment. The danger lies in overpaying for average talent, which would rapidly drain the budget and erode depth; that’s perhaps why CU hasn’t been as busy this spring transfer portal season as many expected.

Colorado’s success will ultimately come down to how well Deion Sanders, Reggie Calhoun Jr., and the rest of the staff is able to balance elite talent with value. If Colorado can be ahead of the game with this balance, they could become the model for roster construction in college football’s new era. If not, they might just become another team stuck with a few stars—and nothing around them.

Great read. Thanks Grant.

Thank you, well researched and answers a lot of questions. If we fully fund, we should be in a position to land top talent, and this portal cycle which was perhaps sub par would be an aberration.